Written by Tanzi Stewart-Stewart

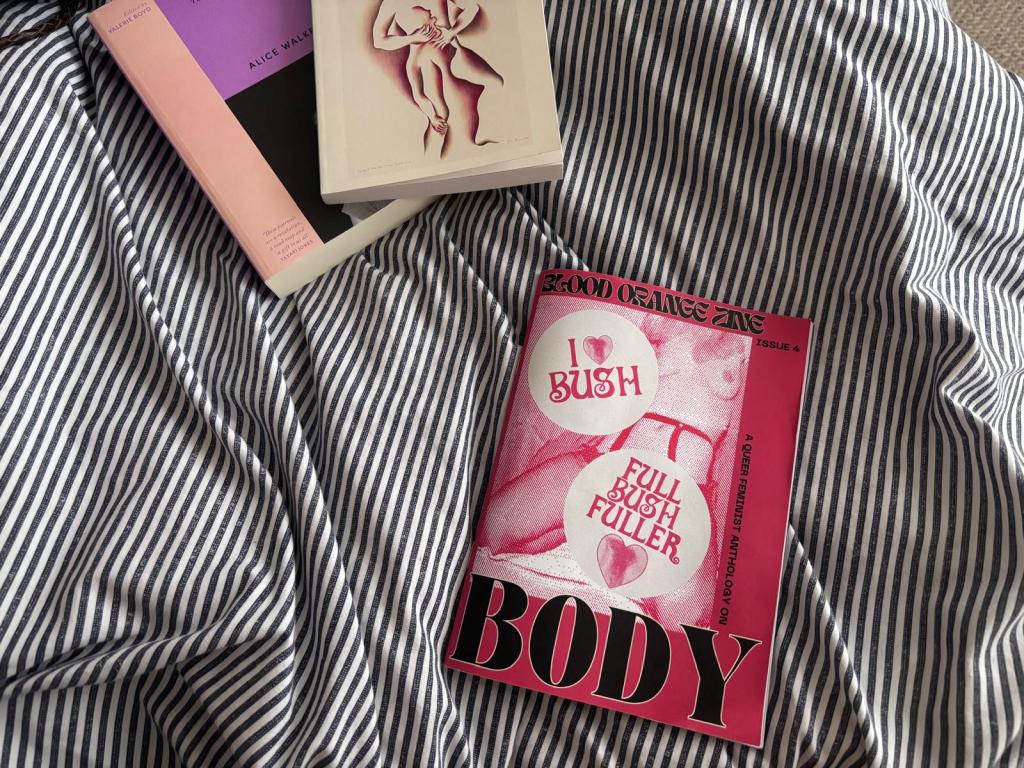

Loyal listeners may remember Sophie McQue from her interview about her and her friend Rosie’s feminist book club, Tongues of Stone. But a book club is dedicated to other authors, and Sophie herself has recently been published in a feminist zine, Blood Orange Zine, based here in Liverpool.

Sitting in Sophie’s bedroom now, it is every inch a bohemian muse’s boudoir draped in white lace and adorned with biblical iconography. Even my interviewee herself is decorated similarly, with a stick and poke of the virgin mary on one arm and ropes of pearls and crosses cascading over her other shoulder. She is an atheist, of course.

I previously interviewed Sophie on The Young Ones on the topic of young women in literature in Liverpool. On that note, Blood Orange is a queer feminist zine, with themes such as female rage, female friendships, and reclaiming the night. Their most recent publication was on the theme of Body, and both Sophie’s first publication and public poetry reading. I enjoyed my first interview with Sophie so much, and am so interested in the topic myself, that I wanted to revisit her on the occasion of her first publication.

How did you approach the body brief?

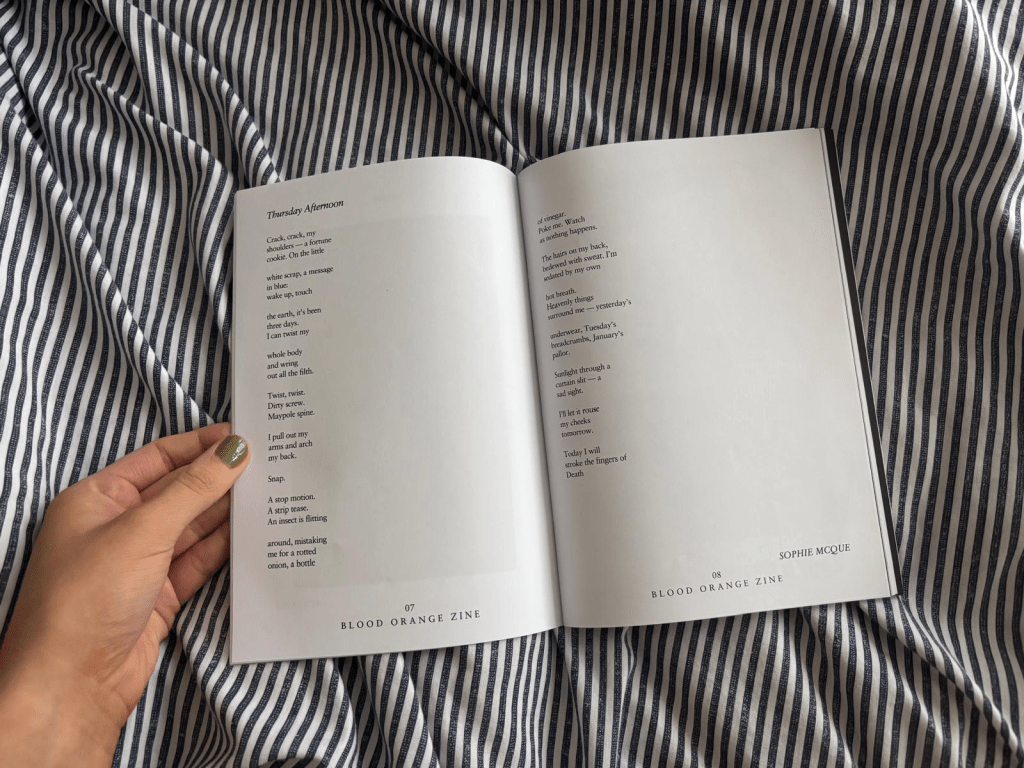

‘I already had poems written. I had actually submitted to their female friendships theme but they didn’t publish it. But this next theme, body, I always write from the body about the body, and they published it. I always use themes of the grotesque…’

Is the female body inherently political to you?

“Yeah. Yes of course… Females have always been kind of looked at through their body and been put at a disadvantage for that. However, I don’t tend to always explore that in my writing. I explore the grotesque. Because I think women’s bodies are often expected to be held up as clean and sexy in a lot of media and I like to confront the abject and the grotesque in my writing. I like to beautify the ugly and uglify the beautiful. I confront the grotesqueness of my body while using very feminine and floral language. I use a lot of animal imagery, feminine colours, and stuff. Delicate things that represent femininity – it makes it a bit creepier I think, approaching the abject from a hyper-feminine angle.”

What was the reading like?

Well.. I mean I was terrified! And they forgot about me. There was a woman there, the creator of the magazine’s old tutor, and she went up and reminded her, so I was the closing act which was daunting for my first ever reading.. However by the end of it I was a little bit tipsy so that helped! I felt empowered- I got a nice cheer from all my friends, and I felt proud of my writing. I just had a feeling that it would be something people resonated with. It gave me confidence knowing that I could read my work with a northern accent. I speak a little bit drab. All my vowels are quite… What’s the word… flat?

(Sophie is from the North-East, with a Mackem accent.)

Final Question… What’s your favourite line from your poem?

Oooh! Dirty screw. May pole spine

For a deeper discussion on women in literature, I encourage you to revisit our broadcast on young women in literature where I originally interviewed Sophie on her book club, available below (Interview begins at 27:58).

You can find Sophie’s work on @dreamboatsophie on instagram and her book club at @tonguesofstone. You can find Blood Orange Zine and their upcoming summer zine at https://bloodorangezine.com/.